34th Annual Scientific Meeting proceedings

Date/Time: 05-07-2025 (09:30 - 10:00) | Location: Gorilla 1

Key points

- What is the environmental impact of the operating theatre and how can we reduce the environmental impact, whilst maintaining quality of care?

- Update on changes in the human surgery field for environmental sustainability.

- Review of the evidence behind single-use items in the operating theatre.

- Introduction of the concept of sustainability quality improvement (SusQI), Lean Service Delivery and the principles of Sustainable Surgical Practice.

“The continued lack of awareness about the effect that the provision of health care has on the health of the ecosystem represents a very real risk to the long-term sustainability of our health care system and our planet. … The operating room is a disproportionate contributor to health care waste and represents a high-yield target for change.” - Kagoma et al., 2012 [1]

Where are we now?

Our planet and its inhabitants currently face a myriad of ecological crises, including climate change, biodiversity collapse, plastic pollution and resource scarcity. Climate change has been described as the biggest global health threat of the 21st century [2] However, global health care exacerbates climate change and is estimated to have twice the carbon footprint of the aviation industry [3]. Whilst veterinary health care is not as egregarious, in terms of resource use, when compared to the human sector, as specialist surgeons we have a comparable impact.

The operating theatre has a particularly high environmental impact [1, 3]. Systematic review of the carbon footprint of operating theatres has been performed in the human sector [4] and identifies the key hotspots for carbon footprint to be procurement of consumables and pharmaceuticals, electricity use and anaesthetic gases; this data is broadly relevant for the veterinary sector too [4].

Desire for change

Within the human healthcare sector, there is now an increasing recognition of the environmental impact of surgery and investigation of opportunities to reduce this impact [1, 3]. Surveys demonstrate increasing surgeon awareness of the climate impact of theatre practice and a willingness to make changes [5, 6], however there is a general desire for guidelines regarding how changes for sustainability can safely be made [7]; these sentiments are echoed in the veterinary sector [8].

Surgical asepsis, infection control and reuse

The success of modern surgery is dependent upon surgical asepsis. Since the advent of modern plastics in the 1980s, medical technology has been revolutionised, providing new standards of care: polymer materials allowing safe sterile intravenous catheterisation, for example. However, contemporaneously, a transformative shift to single-use items has occurred throughout medicine and surgery, replacing previously reusable items, such as surgical drapes and surgical gowns. Single-use disposable surgical textiles have been marketed as gold standard in recent decades, however review of the evidence does not demonstrate improved performance or lower incidence of surgical site infection [9-11]. The performance of modern reusable surgical gowns and drapes has been demonstrated to be superior to their single-use counterparts [12]. It has been suggested that the carbon footprint of reprocessing reusables results in the overall environmental impact of reusables being equivalent to single-use - this is not true. Vozzola, Overcash [13] performed a comprehensive life cycle analysis, comparing the environmental impact of single-use versus reusable surgical gowns, with regards to energy consumption, water use, global warming potential and generation of waste, documenting the significantly higher environmental impact of single-use textiles.

Single-use surgical textiles have widely been adopted in higher socioeconomic counties in human healthcare, whilst reusable surgical textiles have continued to be used in healthcare systems of less affluent countries. This has mirrored in the veterinary sector, with referral veterinary hospitals more broadly adopting single-use textiles. Veterinary in primary care practices have aspired to switch to single-use surgical textiles in the veterinary sector, due to a perception that this reflects gold standard care. However, increasingly within human healthcare, a switch has been made to high quality modern reusables surgical textiles, affording a huge reduction in carbon footprint and financial cost [3]. As we strive for optimal quality of care, and emulate standards in the human operating theatre, it is important that the veterinary sector recognises that single-use is no longer synonymous with the highest quality of care. Some modern human healthcare systems have reported a switch to reusable surgical textiles for orthopaedic surgery, including joint replacements [3].

It is essential that a thorough reprocessing facility, with monitoring of materials and number of uses, is available to guarantee optimal laundering and resterilization. Surgical site infection increases the length of hospitalisation [14] and consequently increases the carbon footprint of patient care, as each day of hospitalisation has an associated environmental impact [15]. It is essential for quality of care and patient welfare that any change for environmental sustainability does not increase the rate of surgical site infection; if the rate of surgical site infection increased then the environmental impact of healthcare would also significantly increase [16].

What is the future?

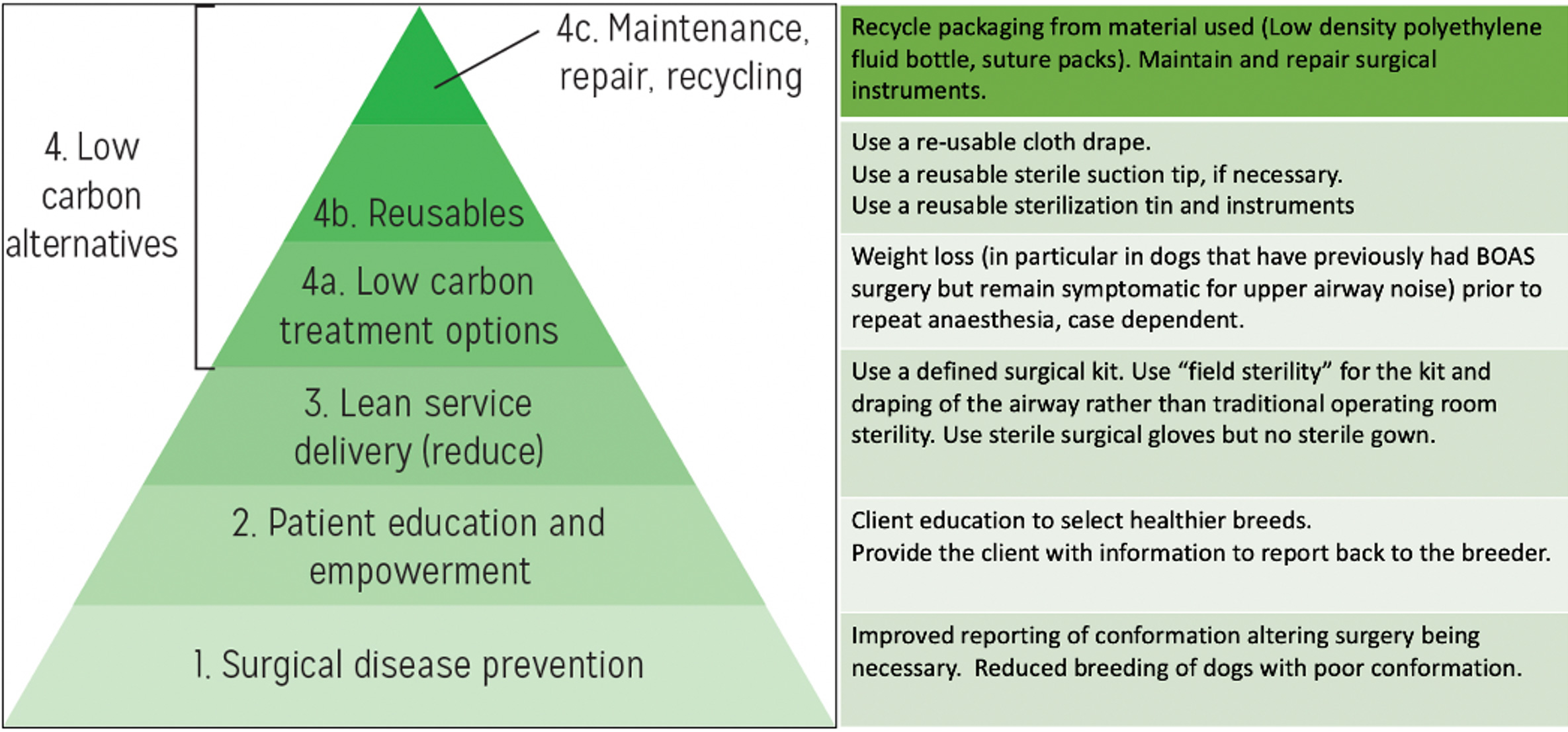

Whilst details of alternative products (e.g., replacing single-use surgical instrument wrap with reusable sterilisation tins) or changes in operational practices (e.g., lower flow gaseous anaesthesia, proper waste segregation) are important in reducing our environmental impact, there is a far broader change in culture and thinking that underpins transformational change to achieving sustainable surgical practice. The Principles of Sustainable Surgery have been described [17] and can be extrapolated to the veterinary section (Figure 1). Lean service delivery is a concept of efficient use of time and resources, and is relevant to reducing the environmental impact of our clinical activities, alongside saving time and cost [17]. Sustainable Quality Improvement (SusQI) is a concept that includes the lens of environmental sustainability when improving quality of care, along with all other domains [18]. Numerous studies have been performed in the human sector to determine the carbon footprint of a specific surgery [13,14,15] and some work is beginning done in the veterinary sphere [16].

As ECVS specialists, residents or experienced surgeons now or in the future, we have great potential for influence. We can make changes to reduce our environmental impact in our operating theatre and hospitals and we can communicate and educate the need and rational basis for these changes to our colleagues and those we teach.

Figure 1. The pyramid representing the Principles of Sustainable Surgical Practice with the table on the right-hand side applying these principles to surgery for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome, for example. Adapted from: Using Surgical Sustainability Principles to improve planetary health. [17]

References

- Kagoma, Y.K., et al., People, planet and profits: the case for greening operating rooms. Cmaj, 2012. 184(17): p. 1905-11.

- Costello, A., et al., Managing the health effects of climate change: <em>Lancet</em> and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. The Lancet, 2009. 373(9676): p. 1693-1733.

- Bhutta, M. and C. Rizan, The Green Surgery report: a guide to reducing the environmental impact of surgical care, but will it be implemented? The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2024. 106(6): p. 475-477.

- Rizan, C., et al., The Carbon Footprint of Surgical Operations: A Systematic Review. Ann Surg, 2020. 272(6): p. 986-995.

- Sathe, T.S., et al., Perspectives on sustainability among surgeons: findings from the SAGES-EAES sustainability in surgical practice task force survey. Surg Endosc, 2024. 38(10): p. 5803-5814.

- Harris, H., M. Bhutta, and C. Rizan, A survey of UK and Irish surgeons’ attitudes, behaviours and barriers to change for environmental sustainability. The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2021. 103(10): p. 725-729.

- Bharani, T., et al., Impact of climate change on surgery: A scoping review to define existing knowledge and identify gaps. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 2024. 15: p. 100285.

- Higham, L.E., et al., Sustainability policies and practices at veterinary centres in the UK and Republic of Ireland. Veterinary Record, 2023. 193(3): p. e2998.

- Ledda, V., et al., The implementation of reusable drapes and gowns in operating theatres: A mixed-methods analysis of data from 5230 peri-operative professionals in 134 countries. Implement Sci Commun, 2025. 6(1): p. 70.

- WHO, WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee, in Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. 2018, World Health Organization © World Health Organization 2018.: Geneva.

- Vasanthakumar, M., Reducing Veterinary Waste: Surgical Site Infection Risk and the Ecological Impact of Woven and Disposable Drapes. Veterinary Evidence, 2019. 4.

- McQuerry, M., E. Easter, and A. Cao, Disposable versus reusable medical gowns: A performance comparison. Am J Infect Control, 2021. 49(5): p. 563-570.

- Vozzola, E., M. Overcash, and E. Griffing, An Environmental Analysis of Reusable and Disposable Surgical Gowns. Aorn j, 2020. 111(3): p. 315-325.

- Seidelman, J. and D. Anderson, Surgical Site Infection Prevention: A Review. JAMA, 2023. 329: p. 244-252.

- Prasad, P.A., et al., Environmental footprint of regular and intensive inpatient care in a large US hospital. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2022. 27(1): p. 38-49.

- Bolten, A., et al., The carbon footprint of the operating room related to infection prevention measures: a scoping review. J Hosp Infect, 2022. 128: p. 64-73.

- C, R., et al., Using surgical sustainability principles to improve planetary health and optimise surgical services following the COVID-19 pandemic. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2020. 102(5): p. 177-181.

- Mortimer, F., et al., Sustainability in quality improvement: measuring impact. Future Healthcare Journal, 2018. 5(2): p. 94-97.