34th Annual Scientific Meeting proceedings

Date/Time: 04-07-2025 (09:15 - 10:00) | Location: Darwin Hall

“Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”― Otto von Bismarck

"To make no mistakes is not in the power of man; but from their errors and mistakes the wise and good learn wisdom for the future"- Plutarch

Introduction

What is a mistake – there are many definitions; The Cambridge Dictionary gives a meaning that works well in a surgical context; being described as ‘an action, decision, or judgment that produces an unwanted or unintentional result’ (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/mistake). We all make mistakes, since to err is human, the key is to learn from them, and importantly that we try to eliminate mistakes before they occur and be as well prepared as we can be, so that the risk of error is minimised.

It is essential that we understand the anatomy, the procedure and the potential complications that can occur in carrying out a TECA/LBO in both the dog and cat 1–8. In addition, we not only need to learn how to deal with adverse events when they do occur but also teach our mentees how to manage adverse situations when they arise 9–15 .

The focus of this presentation will be on understanding the complications that can occur, to minimise the risk of them occurring and how to deal with them as a surgeon and as team in the operating theatre. The potential complications fall into 3 periods intraoperative, immediately postoperative and late postoperative5–7 .

Dealing with a complication

Severe haemorrhage though rare is a potentially life threatening event and it is essential to know where the possible sources are and what can be done to stop it. It’s not just knowing the anatomy but having the tools to deal with the situation if it arises. To this end there is a need to be prepared as an individual and as a team on the operating theatre.

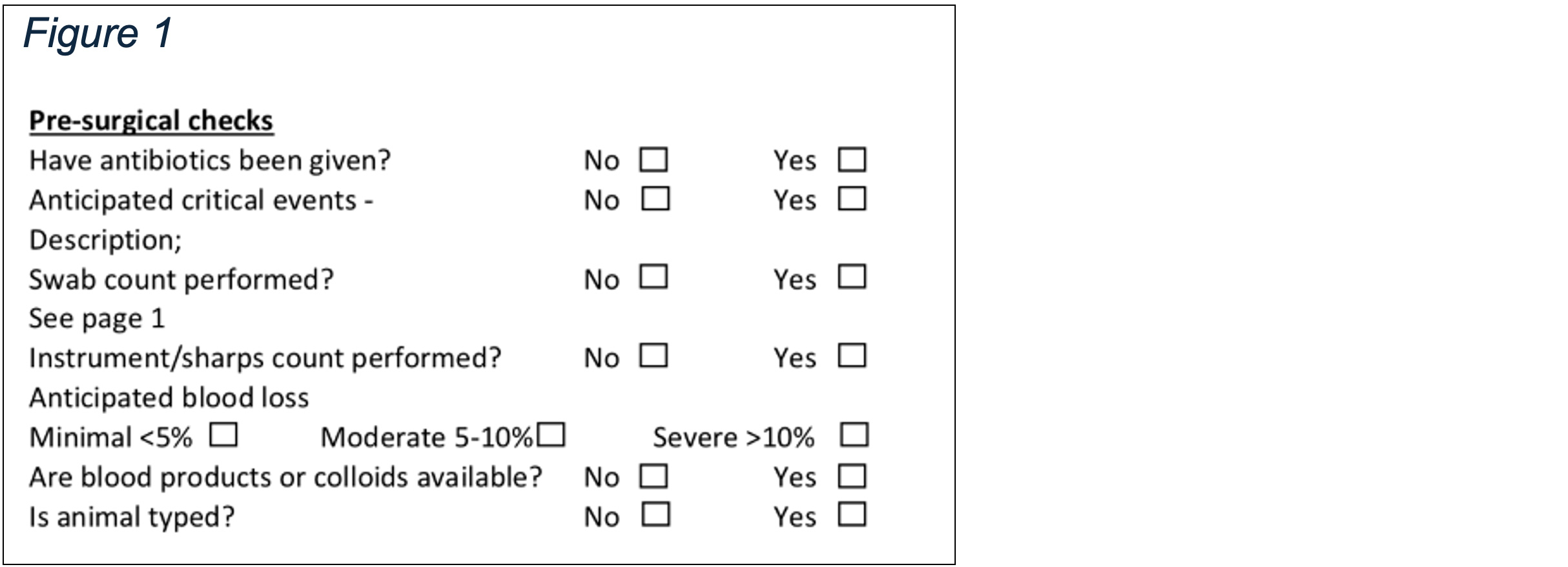

This in my view is where pre surgery checklists come into their own. That’s all well and good but going through a checklist takes time and we’re all busy surgeons and nurses. However, if it saves a life, it is time well spent. Studies from hectic human critical care facilities have shown that using a checklist in a crisis is associated with a six-fold reduction in failure to adhere to critical steps in the management of the emergency. Essentially it helps avoid missing crucial steps in highly pressurized situations and have shown a greater than one-third reduction in complications 16,17 . Some of the key questions on our checklist are based around critical events (Fig1). During the ‘time out’ when these questions are being asked is the ideal time for the theatre team to discuss the potential risk of haemorrhage and what can be done to mitigate it. This period is also key to reduce any perceived hierarchical gradients in the team. It is essential that all those involved in that case are able to speak up without any fear of any come back12 . Two highly effective questions that should be asked during the time out are:

- what if..?

- what am I expected to do if something goes wrong?

This prepares the team for possible complications,

- “what if?” situations will have been discussed and will therefore be fresh in our minds.

Every member of the team should know in advance their role in the unlikely event of a major problem or complication.

The surgeon should be prepared, knowing their anatomy, that the likely vessels they could traumatise, namely the emissary vein of the retroarticular or retroglenoid foramen, the internal maxillary vein and less likely the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries. It is essential to have requested electrocautery or vessel sealing device together with either a topical haemostatic agent or bone wax. During the time out the team will become aware that there is a risk of severe haemorrhage and can ensure that there are blood products or colloids readily available should they be needed. The decision may also be made to blood type if the surgeon is concerned or relatively inexperienced.

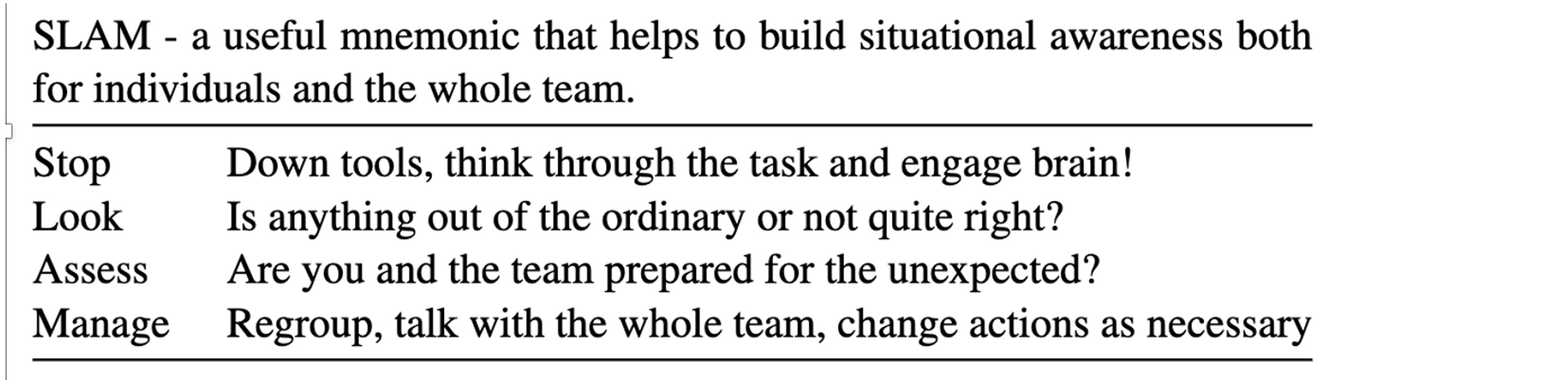

How should we deal with a severe haemorrhage? This is where building situational awareness (SA) in the individual and the team is so important12,18 . The use of simple mnemonics such ‘SLAM’ (Fig 2) or STOPS (Fig 3) can help build SA in an individual and in the team12 .

Figure 2 (from Brennan et al 2020)12

Clearly stopping completely should only be done if it is safe to do so in the circumstances19 . With severe haemorrhage the first step would be to pack the wound with surgical swabs and apply pressure. Then you can stop and think – where is it most likely to be bleeding from. The surgeon should take this time to inform the team of the issue and request topical haemostatic agents and/or bone wax to be opened, if they had not been previously. By communicating in this way, the team can be prepared to send for blood products or colloids or contact other clinicians such as anaesthetists or ECC in case they are needed. The surgeon should not be dealing with the haemorrhage in isolation.

After a period of reflection the swabs should be removed and the source of the haemorrhaging identified. There may of necessity be a need to repack or use suction if the haemorrhage obscures the structures deep in the wound. Ideally there should be an assistant surgeon who can help retract tissues and use the suction tip whilst the primary surgeon deals with the haemorrhage. Bone wax after it has been softened can be packed into the retroarticular/retroglenoid foramen, and the bulla (it must be removed from the bulla before wound closure). Diathermy rarely works on the emissary vein as it retracts into the foramen. Alternately a topical haemostatic agent can be applied. Traumatised arteries and veins should be sealed with diathermy or a vessel sealing device.

Post Surgery

Regardless of whether the error was dealt with well or not there should be a debrief session, it is essential that no individual should try to cope with difficult situations and outcomes in the ‘silo of silent surgical culture’20,21 .

The presentation will expand on these themes.

References

- Smeak DD, Dehoff WD. Total Ear Canal Ablation Clinical Results in the Dog and Cat. Vet Surg. 1986;15:161–170.

- Mason LK, Harvey CE, Orsher RJ. Total Ear Canal Ablation Combined with Lateral Bulla Osteotomy for End‐Stage Otitis in Dogs Results in Thirty Dogs. Vet Surg. 1988;17:263–268.

- White RAS, Pomeroy CJ. Total ear canal ablation and lateral bulla osteotomy in the dog. J Small Anim Pr. 1990;31:547–553.

- Williams JM, White RAS. Total ear canal ablation combined with lateral bulla osteotomy in the cat. J Small Anim Pr. 1992;33:225–227.

- Bacon NJ, Gilbert RL, Bostock DE, White RAS. Total ear canal ablation in the cat: indications, morbidity and long‐term survival. J Small Anim Pr. 2003;44:430–434.

- Smeak DD. Management of Complications Associated with Total Ear Canal Ablation and Bulla Osteotomy in Dogs and Cats. Vet Clin North Am: Small Anim Pr. 2011;41:981–994.

- Coleman KA, Smeak DD. Complication Rates After Bilateral versus Unilateral Total Ear Canal Ablation with Lateral Bulla Osteotomy for End‐Stage Inflammatory Ear Disease in Dogs: 79 Ears. Vet Surg. 2016;45:659–663.

- Mehrkens LR, Townsend KL, Cooley SD, Milovancev M, Newsom LE. Experience level as a predictor of entry into the hypotympanum during feline total ear canal ablation and lateral bulla osteotomy. J Feline Med Surg. 2021;23:900–905.

- Cohen-Hatton SR, Butler PC, Honey RC. An Investigation of Operational Decision Making in Situ. Hum Factors J Hum Factors Ergonomics Soc. 2015;57:793–804.

- Robertson R, Hill AG. Building resilience in the face of adversity: the STRONG surgeon. Anz J Surg. 2020;90:1766–1768.

- Flin R, Youngson G, Yule S. How do surgeons make intraoperative decisions? Qual Saf Heal Care. 2007;16:235.

- Brennan PA, Holden C, Shaw G, Morris S, Oeppen RS. Leading article: What can we do to improve individual and team situational awareness to benefit patient safety? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:404–408.

- Gogalniceanu P, Kessaris N, Karydis N, Calder F, Mamode N. Responding to Unexpected Crises – The Role of Surgical Leadership. Ann Surg. 2020;272:937–938.

- D’Angelo JD, Lund S, Woerster M, et al. STOPS. Ann Surg. 2022;276:288–292.

- D’Angelo A-LD, Kapur N, Kelley SR, et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Operative staff perspectives of surgeon coping with intraoperative errors. Surgery. 2023;174:222–228.

- Ziewacz JE, Arriaga AF, Bader AM, et al. Crisis Checklists for the Operating Room: Development and Pilot Testing. Journal of the American College of Surgeons . 2011 Aug 1;213:212-217.e10.

- Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Dziekan G, et al. Effect of a 19-item surgical safety checklist during urgent operations in a global patient population. Annals of Surgery [Internet]. 2010 May;251:976–980.

- Graafland M, Schraagen JMC, Boermeester MA, Bemelman WA, Schijven MP. Training situational awareness to reduce surgical errors in the operating room. Br J Surg. 2015;102:16–23.

- Hardie JA, Brennan PA. Human factors in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: a short overview. Orthop Trauma. 2024;38:124–129.

- Luby AO, Chung KC. Shedding Light on Surgeons’ Darkest Times: Coping with Errors and Stress in the Silos of a Silent Surgical Culture. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024;154:261–264.

- Kogan LR, Rishniw M, Hellyer PW, Schoenfeld-Tacher RM. Veterinarians’ experiences with near misses and adverse events. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2018 Mar;252:586–595.