34th Annual Scientific Meeting proceedings

Date/Time: 04-07-2025 (10:45 - 11:15) | Location: Marble Hall

What is PADS

Patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome (PADS) is a bone disease in cats. It usually affects young cats (1-3 years) who develop spontaneous patella fractures that are mid body and transverse (Fig 1). Following fracture of one patella the contralateral patella will often fracture, on average 3m later. Non-union patellar fractures can be seen in older cats (1).

Fig 1. Transverse mid body patellar fracture in a cat with PADS. Note the sclerosis of the bone.

In some cats the first sign they have PADS may be persistent or retained deciduous teeth. The permanent teeth can fail to erupt (retained teeth) predisposing to maxillary or mandibular abscessation and osteomyelitis (2). A small subset of affected cats (<5%) have been reported to develop nail bed infections or paronychia which is resistant to medical management and only resolves with amputation of P3 (3).

Stress insufficiency fractures

Radiographic changes with stress fractures include increased density / sclerosis, cortical thickening and consistency of fracture lines. A radiolucent defect may be seen prior to fracture. In humans ‘the dreaded black line” is a subtle radiographic sign for a unique type of high-risk stress fracture in anterior tibial cortex, a similar sign can be seen in the tibia of PADS cats (Figure x) (4).

Repetitive response to stress leads to osteoclastic activity that surpasses the rate of osteoblastic new bone formation, resulting in temporary weakening of bone. If the physical activity is continued, trabecular microfractures result. The bone responds by forming periosteal new bone for extra reinforcement. However, if the osteoclastic activity continues to exceed the rate of osteoblastic new bone formation, eventually a full cortical break occurs (4). Stress fatigue fractures occur due to abnormal forces on normal bone. Insufficiency fractures occur following normal forces on abnormal bone, the latter is thought to be occurring in PADS cats.

Fig 2. A dreaded black line in the cranial cortex of a tibia of a cat and multiple ‘dreaded black lines’ in the tibia of a human football player (4). The fractures lies are occurring on the tension side of the bone and there is sclerosis around the lines and cortical thickening compatible with stress fractures.

Histological analysis of bone from PADS cats has shown osteopetrosis (bell) and fracture, abnormal teeth development and an increased rate of bone infection are seen with osteopetrosis.

Bisphosphonate induced fractures in cats

There are several publications in the literature on cats on long term bisphosphonates fracturing bones and developing jaw necrosis (5,6,7), there are also multiple references of insufficiency fractures occurring in humans on long term bisphosphonates. Bisphosphonates interfere with osteoclast action and people with osteopetrosis have fewer or abnormal functioning osteoclasts.

Fractures of other bones

Cats with PADS are at risk of developing subsequent (or preceeding) atraumatic fractures in other bones. The fractures of other bones often occur bilaterally, may occur at different times to each other and are often of similar configurations. The most commonly reported fractures are acetabular, ischial, humeral condylar, proximal tibia, calcaneal and femoral neck, accessory carpal bone and spine less commonly (8).

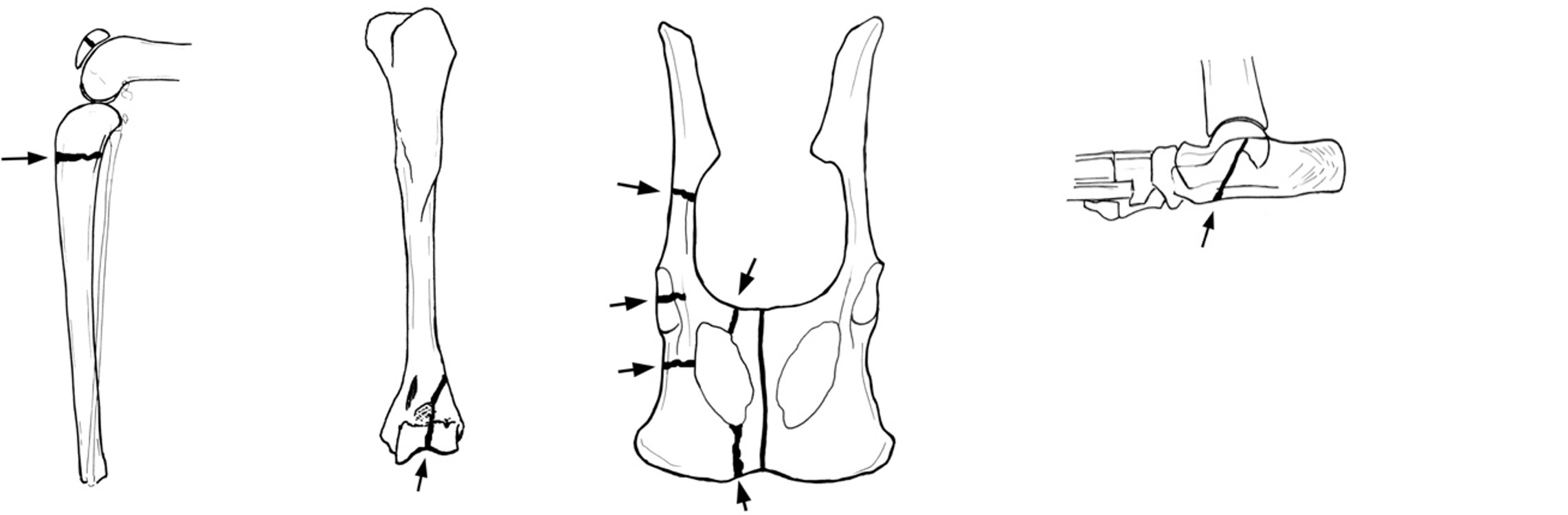

Fig 3. Common orientation of fractures in tibia, humerus, pelvis and calcaneus in cats with PADS

Tibial fractures are usually proximal in location and transverse (Fig 3, Fig 4) (9).

Fig 4. Classic location of a tibial insufficiency fractures in a cat with PADS. The patella fracture is chronic and sclerotic with osteoproliferation that can be seen in the older fracture, probably in an attempt at healing.

Humeral fractures - just under 10% of PADS cats are reported to develop humeral intracondylar fractures (10). There is evidence of a fissure in the bone (HIF or humeral intracondylar fracture) in some cats (10, 11).

Pelvic fractures are the most common fractures to occur (25%). Fractures affect the ischium, pubis, ilium, and acetabulum (Fig 5). The acetabulum is the most commonly reported (5).

Calcaneal fractures are oblique (Fig 5) & often bilateral either at first presentation or subsequently (12).

Spinal and other fractures

Fractures have also been reported to affect other bones in rare instances (5). These include the spine, femoral neck, accessory carpal bone. The cats presenting with spinal fractures presented to the veterinarians with severe neurological issues and in many cases are euthanased.

References

- Langley-Hobbs SJ. Survey of 52 fractures of the patella in 34 cats. Veterinary Record 2009 164, 80-86

- Howes C, Longley M, Reyes N, Major AC, Gracis M, Fulton Scanlan A, et al. Skull pathology in 10 cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21(8):793-800.

- Pilot MA, Bell C, O'Dair H, Glenn EJ, Bailey S, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Chronic paronychia in cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg. 2021 Mar 24:1098612X21998612.

- Fredericson, Michael MD*; Jennings, Fabio MD*; Beaulieu, Christopher MD, PhD†; Matheson, Gordon O. MD, PhD*. Stress Fractures in Athletes. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging 17(5):p 309-325, October 2006. | DOI: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e3180421c8c

- Meneghetti LM, Perry KL. Management of insufficiency fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate therapy in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2023 Aug 12;9(2):20551169231183752.

- Council N, Dyce J, Drost WT, de Brito Galvao JF, Rosol TJ, Chew DJ. Bilateral patellar fractures and increased cortical bone thickness associated with long-term oral alendronate treatment in a cat. JFMS Open Rep. 2017 Aug 29;3(2):2055116917727137.

- Larson MJ, Oakes AB, Epperson E, Chew DJ. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after long-term bisphosphonate treatment in a cat. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Mar;33(2):862-867.

- Reyes NA, Longley M, Bailey S, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Incidence and types of preceding and subsequent fractures in cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg 2019; 21: 750-764.

- Langley-Hobbs SJ, Ball S, McKee WM Fracture of the tibia associated with chronic patella fractures in cats. Veterinary Record 2009, 164, 425-30

- Chan AJ, Reyes Rodriguez NA, Bailey SJ, Langley-Hobbs SJ. Treatment of humeral condylar fractures and humeral intracondylar fissures in cats with patellar fracture and dental anomaly syndrome. J Feline Med Surg. 2020:1098612x20904458.

- Holloway GL, Midgley D. Lateral condylar fracture secondary to humeral intracondylar fissure in a cat. Vet Surg. 2021 May;50(4):898-903.

- Longley, M., Bergmann, H., & Langley-Hobbs, S. (2016). Case report: calcaneal fractures in a cat. Companion Animal, 21(5), 265-269