34th Annual Scientific Meeting proceedings

Date/Time: 04-07-2025 (11:00 - 11:30) | Location: Okapi 2+3

Orthopedic deformities in foals can be both congenital and acquired. Congenital problems are present at birth and usually obvious. Congenital angular and flexural deformities can lead to dystocia and in some cases, necessitate fetotomy or Caesarean section to relieve the dystocia. Many foals are born with some degree of flexural or angular limb problem. The most common appearance is a degree of flexor laxity and carpal and/or tarsal valgus deformity. Fortunately, these deformities usually self-correct with exercise and age and should be considered normal findings in a newborn foal. Likewise, congenital flexural deformity of both the metacarpal/tarsal phalangeal joint, distal interphalangeal joint and carpus may be present. Mild forms of these conditions will self-correct with age and exercise but in my experience moderate to severe congenital flexural deformity usually requires some type of intervention.

Orthopedic evaluation of a foal can be difficult and foals will often look different inside and outside of a stall. For example, a foal with even a mild lameness may be non-weight bearing when turned in a stall but look much less lame when walked with the mare. Also, it is difficult to accurately assess flexural and angular deformities with a foal standing in a stall. For this reason, it is essential to evaluate conformation and gait with the foal outside of the stall. Historical information regarding conformation of siblings or half-siblings should enter the equation regarding future conformation and management. Likewise, the conformational tendencies of the mare and stallion should be considered as well. The input from farm personnel who have been monitoring the foal is critically important when making management decisions regarding conformation.

Consideration of the entire limb is paramount when deciding on therapies. Conformational abnormalities of the foot should be corrected and use of foot trimming or extension by themselves can be very effective in correcting conformation abnormalities of the fetlock and carpus. Often foals will have opposite conformational abnormalities of the fetlock and carpus. For example, most foals with significant carpal valgus deformities tend to accommodate this problem by developing a fetlock varus deformity. It is important to keep this in mind as the carpus is corrected because failure to address this may lead to a permanent fetlock varus deformity despite a straight carpus. Conversely overly aggressive trimming of a foot to correct a deformity that is best handled with surgery can lead to hoof deformities and lameness.

Most foals are born with some degree of tarsal and carpal valgus deformity. This is generally considered normal. As the foal matures many angular deformities completely improve. Moderate to severe (>10 degrees) valgus deformities that are still present at 6 weeks are considered abnormal and require evaluation. Causes of valgus deformity include ligamentous joint laxity, physeal dysplasia and cuboidal bone abnormalities. Ligamentous joint laxity can be assessed by manipulation of the foal’s limb. Radiographs are required to diagnose physeal dysplasia or cuboidal bone problems. Dorsopalmar radiographs reveal the location of the angular deformity by the center of the angle formed by lines drawn down the center of the metacarpus and radius. If the lines meet in the physis or epiphysis then the abnormality originates from the physis. If the lines meet in the carpus then the source is the cuboidal bones. It should be noted however that concurrent rotational deformities of the limbs may make radiographic interpretation of the exact location of the deformity somewhat inexact. Fortunately, most of the boney causes for angular limb deformities are in the physis, which is more reliably corrected surgically.

Periosteal elevation and transection has been accepted as an effective means of correcting angular limb deformities in growing horses. Although used less frequently in my opinion it still has a place in management of angular deformities in foals.

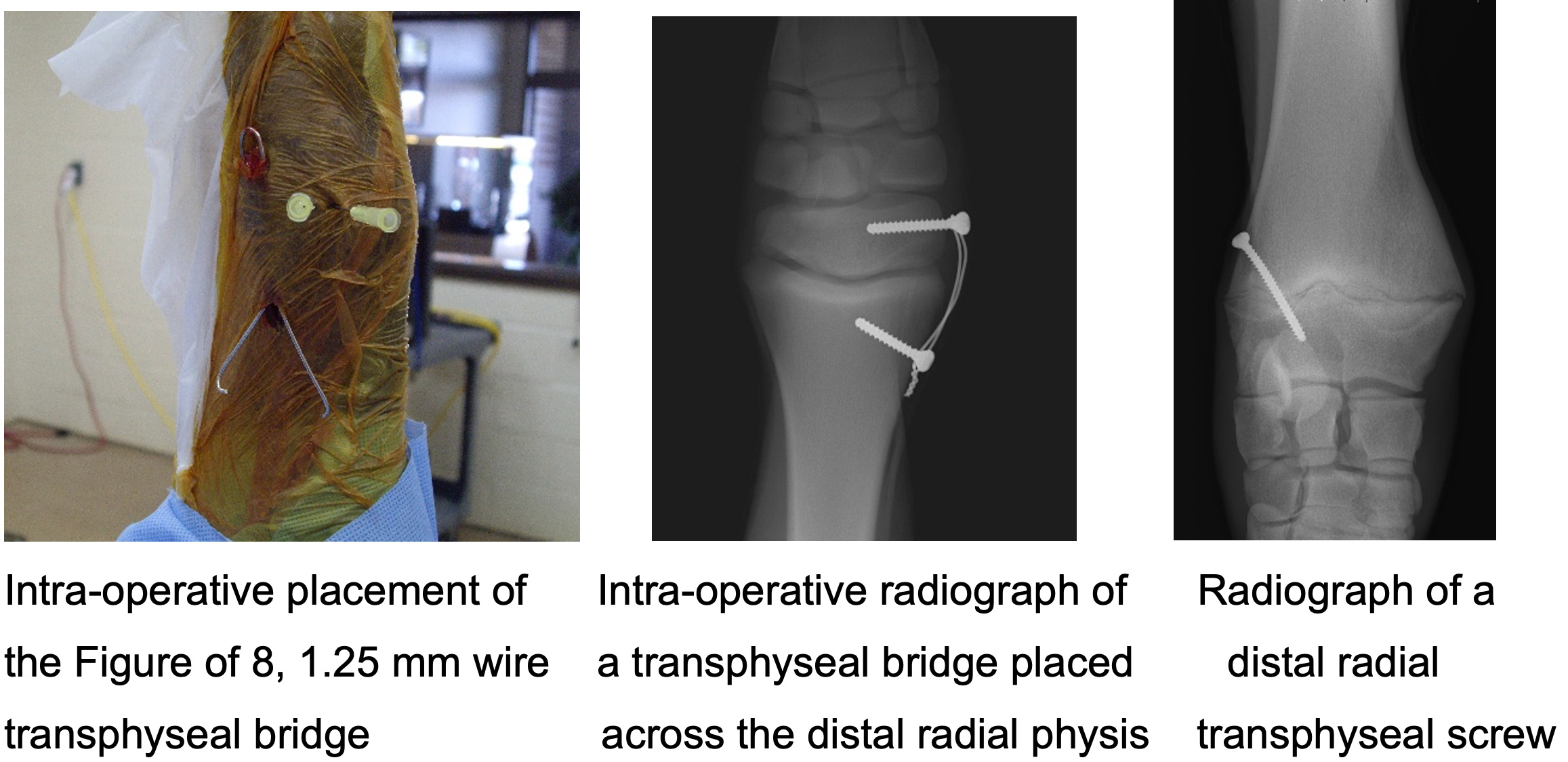

In cases of severe angular deformity or in older foals and yearlings physeal retardation with screws and wires or transphyseal screws are necessary to slow the growth on the “long” side of the bone. In our practice, physeal retardation of the fetlock is exclusively accomplished with transphyseal screws and that of the carpus with screws and wires up thorough approximately 12 months of age > after 12 months it seems to be safe to use transphyseal screws with limited risks of overcorrection of the carpus in yearlings after removal. In the tarsus I am more aggressive with the placement of transphyseal screws in the distal tibia and have used them in foals as young as 4 months of age without overcorrection. I prefer this technique to screws and wire in these cases as they do faster correction, lower risks of incisional complications and improved cosmetic outcome.

Implant removal after physeal retardation is required. If TPS are placed for fetlock deformities overcorrection is rare due to the short window of growth. Carpal deformities have the greatest risk of overcorrection and careful monitoring and prompt removal after correction is required. Removal can be done either with sedation and local block or under general anesthesia. Screw breakage, screw head stripping, bone overgrowth of screw head, wire breakage as well as potential surgical site infection are potential risks of transphyseal bridge placement.